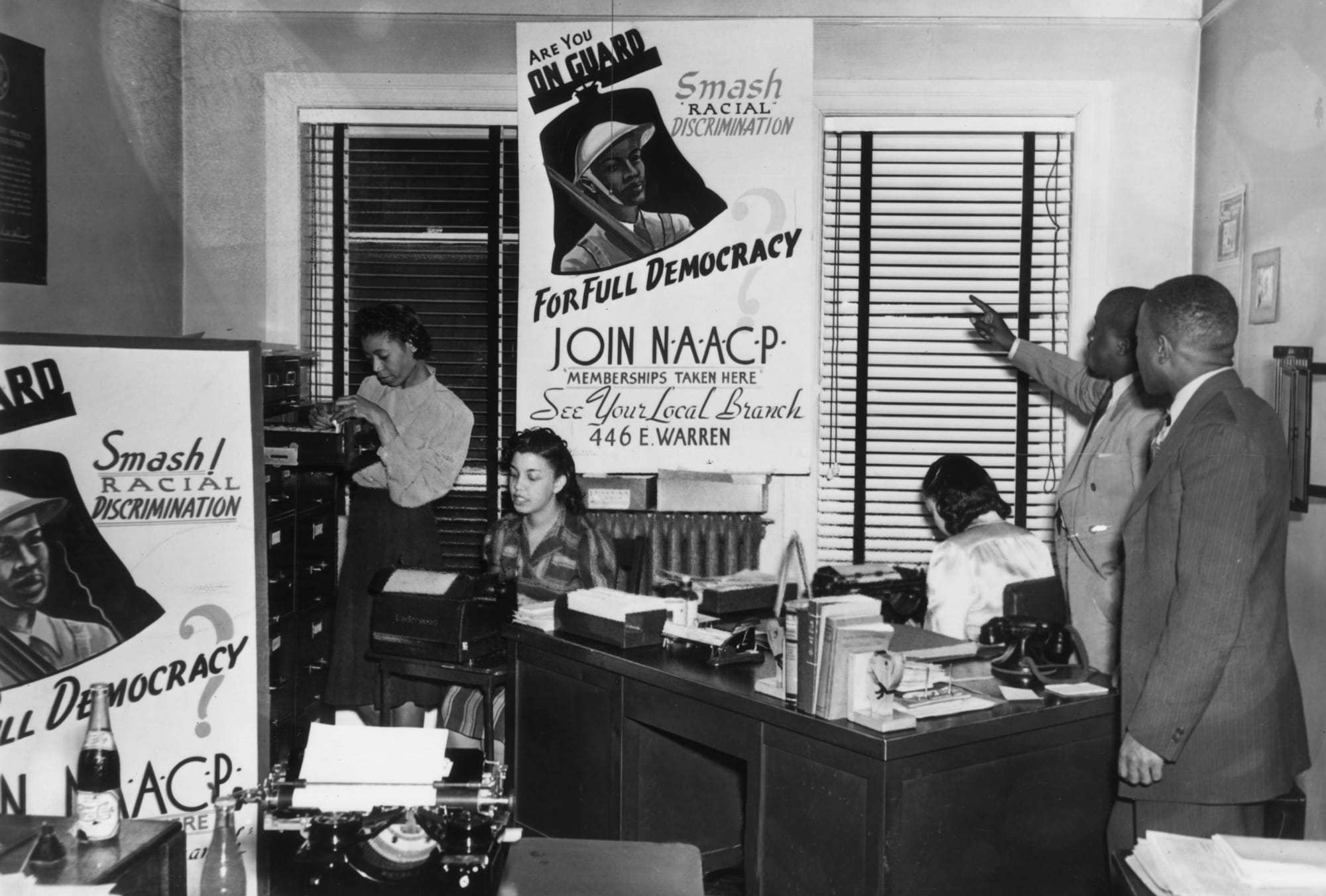

The NAACP is founded

On February 12, 1909, the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, a group that included African American leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells-Barnett announced the formation of a new organization. Called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, it would have a profound effect on the struggle for civil rights and the course of 20th Century American history.

The conference that led to the NAACP’s founding had been called in response to a race riot in Illinois. The founders also noted the disturbing trends of lynchings, which reached their peak not during or immediately after the Civil War but in the 1890s and early 1900s, as segregation laws took effect across the South and white supremacists once again gained total control of state governments. Many of the organization’s early members came from the Niagara Movement, a group created by black activists who were opposed to the concepts of conciliation and assimilation.

In its early years, the NAACP spread awareness of the lynching epidemic by means of a 100,000-person silent march in New York City. It also won a major legal victory in 1915, when the Supreme Court declared an Oklahoma “grandfather clause” that allowed whites to bypass voting restrictions unconstitutional. Perhaps its most famous legal victory came in 1954, when NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund founder Thurgood Marshall won the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision. Marshall went on to become the first African American Supreme Court justice in 1967. In addition to other legal victories during the Civil Rights Era, the NAACP helped organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, as well as the Mississippi Freedom Summer, a seminal voter registration drive. The campaign came two years after an NAACP field secretary, Medgar Evers, was assassinated at his home in Jackson.

Due to its prominent members, landmark legal victories, and lobbying for laws like the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, the NAACP holds a place of distinction in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. It remains the largest and oldest active civil rights group in the nation, and its emphasis on voter registration, legal defense and activism have set an example for subsequent groups to follow.

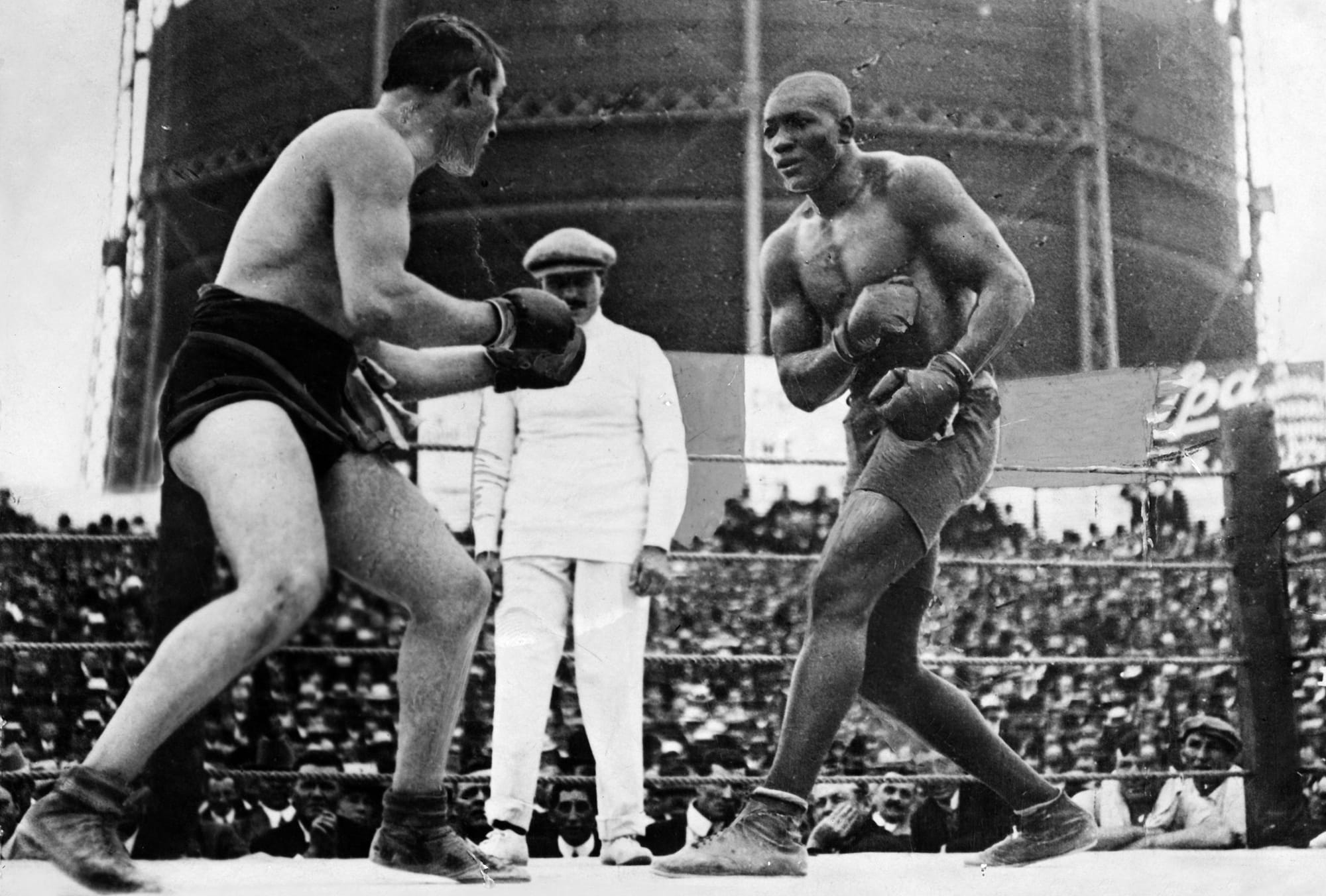

Jack Johnson wins heavyweight title

Jack Johnson becomes the first African American to win the world heavyweight title when he knocks out Canadian Tommy Burns in the 14th round in a championship bout near Sydney, Australia. Johnson, who held the heavyweight title until 1915, was reviled by whites for his defiance of the “Jim Crow” racial conventions of early 20th-century America.

The boxer that is still remembered as the greatest defensive boxer in heavyweight history was born in Galveston, Texas, in 1878. Johnson dropped out of school after fifth grade and worked the docks of Galveston before taking up professional boxing. He proved himself a powerful fighter, but the rarity of champion white boxers agreeing to meet black challengers limited his opportunities and purses. In 1903, Johnson won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World” and the next year issued a challenge to Jim Jeffries, the white American who held the world title at the time. Jeffries refused to meet him, and it was not until 1908 that Tommy Burns agreed to give Johnson a shot at the more prestigious white heavyweight title.

The boxers met at Rushcutter’s Bay on the outskirts of Sydney on December 26, 1908. Few of the 20,000 spectators gathered there cheered Johnson as he dominated Burns and became the heavyweight champion of the world. Johnson’s reception upon returning to the United States was equally lukewarm, and racists were appalled by his marriage to a white woman. Johnson refused to keep a low profile in the face of criticism of his color and character, and instead took on an excessively flamboyant lifestyle. He drove flashy sports cars, flaunted gold teeth that went with his gold-handled walking stick, and engaged in numerous, overlapping romances with women–all of them white. Reporters began calling for a “Great White Hope” to put the heavyweight title back in a white man’s hands.

In 1912, Johnson was convicted of transporting an unmarried woman across state lines for “immoral purposes,” a law that was drafted primarily to prevent prostitution and the white slavery trade–not to prevent a black boxer and nightclub owner from having an affair with his white secretary. Johnson was sentenced to a year in prison and released on bond pending an appeal. He took the opportunity to flee the United States disguised as a member of a black baseball team.

Johnson lived in exile for the next seven years and continued to defend his title in bouts in Europe and elsewhere. On April 5, 1915, he lost the heavyweight title when he was knocked out by white American Jess Willard in the 20th round of a fight in Havana, Cuba. There were rumors that Johnson threw the championship in order to have the charges against him dropped. The charges were not dropped, however, and when Johnson returned to the United States in 1920 he was arrested by U.S. marshals. He was sent to a federal prison in Kansas to serve his year sentence.

After his release, Johnson boxed occasionally but never regained his former stature. His fortunes steadily diminished, and near the end of his life he worked as a vaudeville and carnival performer. He died in a car accident in 1946.

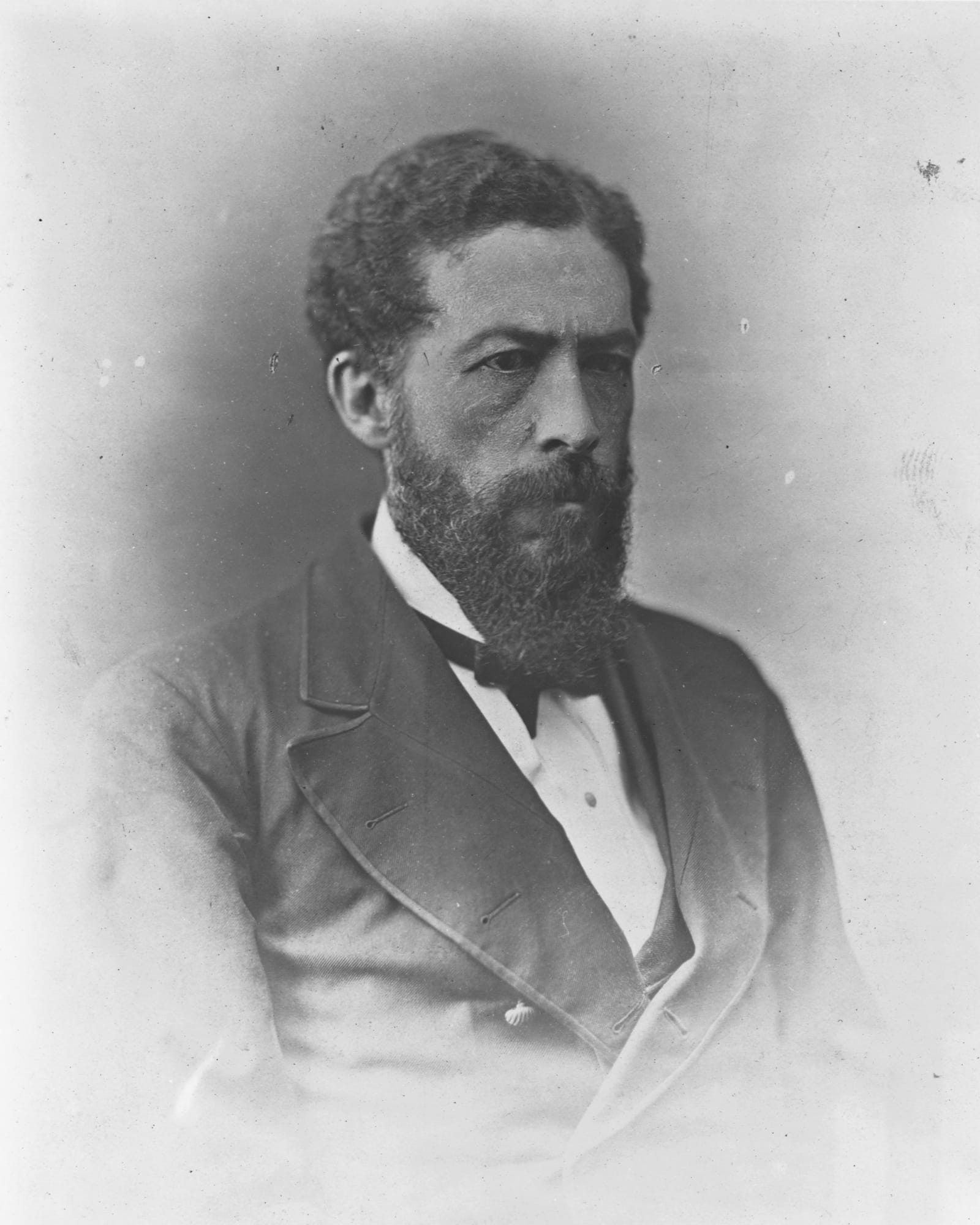

John Mercer Langston

(December 14, 1829 – November 15, 1897) was an abolitionist, attorney, educator, activist, diplomat, and politician in the United States. An African American, he became the first dean of the law school at Howard University and helped create the department. He was the first president of what is now Virginia State University, a historically black college.

Born free in Virginia to a freedwoman of mixed race and a white planter father, in 1888 Langston was elected to the U.S. Congress as the first representative of color from Virginia. Joseph Hayne Rainey, the black Republican congressman from South Carolina, had been elected in 1870 during the Reconstruction era.

In the Jim Crow era of the later nineteenth century, Langston was one of five African Americans elected to Congress from the South before the former Confederate states passed constitutions and electoral rules from 1890 to 1908 that essentially disenfranchised blacks, excluding them from politics. After that, no African Americans would be elected from the South until 1973, after the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed to enforce their constitutional franchise rights.

Langston’s early career was based in Ohio where, with his older brother Charles Henry Langston, he began his lifelong work for African-American freedom, education, equal rights and suffrage. In 1855 he was one of the first African Americans in the United States elected to public office when elected as a town clerk in Ohio.[1][2][3] The brothers were the grandfather and great-uncle, respectively, of the renowned poet Langston Hughes.

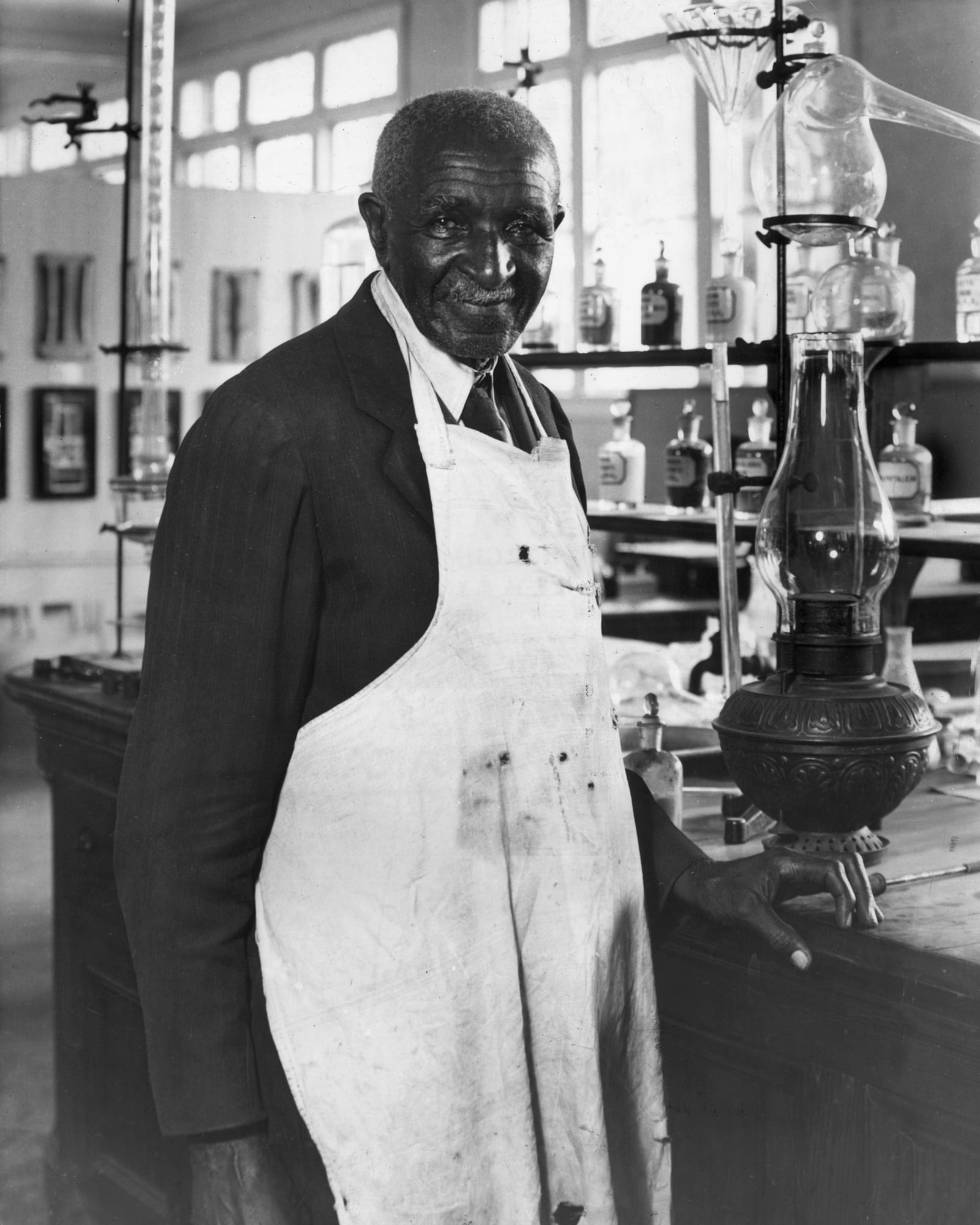

George Washington Carver

One of the most accomplished and famous people of the 20th century, George Washington Carver overcame nearly every obstacle placed in his path to fulfill his lifelong passion for learning, using his hard-earned education to improve the lives of African Americans, and of people living in the deep South.

Carver was born a slave

No documents survive detailing Carver’s birth, but he was likely born around 1864 or 1865, on the farm of Moses Carver, near Diamond Grove, Missouri. His mother, Mary, was owned by Moses Carver, and his father, who died either before or after George’s birth, was enslaved on a nearby farm.

Shortly after his birth, Mary and George were kidnapped by Confederate raiders who hoped to sell them for profit. Moses attempted to track them down but was only able to locate young George, and he never saw his mother again.

Freed from slavery after the end of the Civil War but a sickly youth, George and his brother Jim were raised by Moses and his wife, Susan. The first in a series of couples who recognized and nurtured George’s native abilities and talents, they taught him to read and encouraged his early interest in plants and nature, with Carver working alongside Susan in her garden, and wandering the nearby woods and fields, collecting specimens.

Carver didn’t begin formal education until he was about 12

Unable to attend the local whites-only elementary school, George left the Carvers farm to pursue his education in Neosho, Missouri, where he lived and worked with a black couple, Mariah and Andrew Watkins. Carver learned more about plants and herbs from Mariah’s work as a midwife, but he found himself disappointed in the lack of academic rigor in the local black school.

By the late 1870s, Carver was on the move again. He joined a number of other African-Americans who decided to move west, primarily to Kansas, as part of a mass migration known as the “Exodusters.” He supported himself through odd jobs, before finally graduating from Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas.

When Carver was denied admission to college, he educated himself

Carver received a full scholarship to Kansas’ Highland College, but when he showed up on campus to enroll, school administers refused to admit him — claiming they had been unaware of his race.

Once again, Carver took matters into his own hands. He settled a homesteading claim, where he dedicated his time to assembling an extensive collection of botany and geological specimens.

He eventually made his way to Iowa, where the bright young man once again found support from a local couple, John and Helen Millholand. They encouraged him to enroll in Simpson College, a small school open to all races. Despite his later fame as an agriculturalist, Carver initially studied music and art. (He even showed some of his paintings at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.)

He was the first black student – and faculty member – at Iowa State University

Carver’s art teacher at Simpson, Etta Budd, helped push him towards his life’s work. Fearing that Carver would struggle to make a living as a black artist, and knowing of his lifelong love of plants, Budd convinced Carver to switch his course of study to botany and to transfer to Iowa State University (then known as Iowa State Agricultural College).

Carver was accepted as the school’s first black student and received his bachelor’s degree in agricultural sciences in 1894 when he was around 30 years old. Recognizing his talents, the school asked him to stay on as an instructor while he obtained his master’s degree, which he finished in 1896, becoming the first African-American to earn an advanced degree in the field.

Carver spent more than 40 years at Tuskegee

Shortly after obtaining his master’s degree, Carver was lured away from Iowa by Booker T. Washington. Washington was a prominent educator and the founder of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama.

The school initially focused on offering vocational training for blacks, and in 1896, Washington pursued Carver to lead its new agricultural department.

Although he originally planned on staying at Tuskegee for just a few years, he remained there for the rest of his career. Despite initially limited funding, he soon created a thriving research institute and became a beloved and inspiring teacher to his students.

Like Washington, Carver advocated for increased educational opportunities for African-Americans, although both men were criticized by other black leaders, including W.E.B. Du Bois, who preached a more aggressive, confrontational approach to racism and segregation in America, and attacked Washington and Carver for their focus on vocational skills as a means of advancement.

Carver’s “movable schools” helped save Southern farmers

Carver became a pioneer of emerging agricultural theories like soil conservation and crop rotation, both desperately needed due to an overreliance on growing cotton that left the soil on many southern farms dangerously depleted.

Carver taught agricultural extension programs at Tuskegee and began his decades-long research experiments with alternative crops like sweet potatoes and, most famously, peanuts, developing more than 300 different uses and earning him lasting fame as the “peanut man.”

But Carver realized that low literacy rates across the Deep South and a lack of educational opportunities made it difficult to spread his message where it was needed most. He offered night school classes and abbreviated agricultural conferences held during non-harvesting seasons.

Beginning in 1906, Carver helped organize a series of agricultural schools on wheels that traveled around Alabama offering practical, hands-on lessons and information on everything from crop, seed and fertilizer selection to dairy farming, nutrition and the best types of animals to breed in particular regions. These “moveable schools” reached thousands of people each month and were eventually expanded to include sanitation demonstrations and registered nurses who offered medical advice and assistance.

Carver patented very few inventions, preferring to allow others to benefit from his work. His focus on the importance of education remained a lifelong passion. Upon his death in 1943, he bequeathed $60,000 to establish the George Washington Carver Foundation, which provides funding for black researchers at Tuskegee.

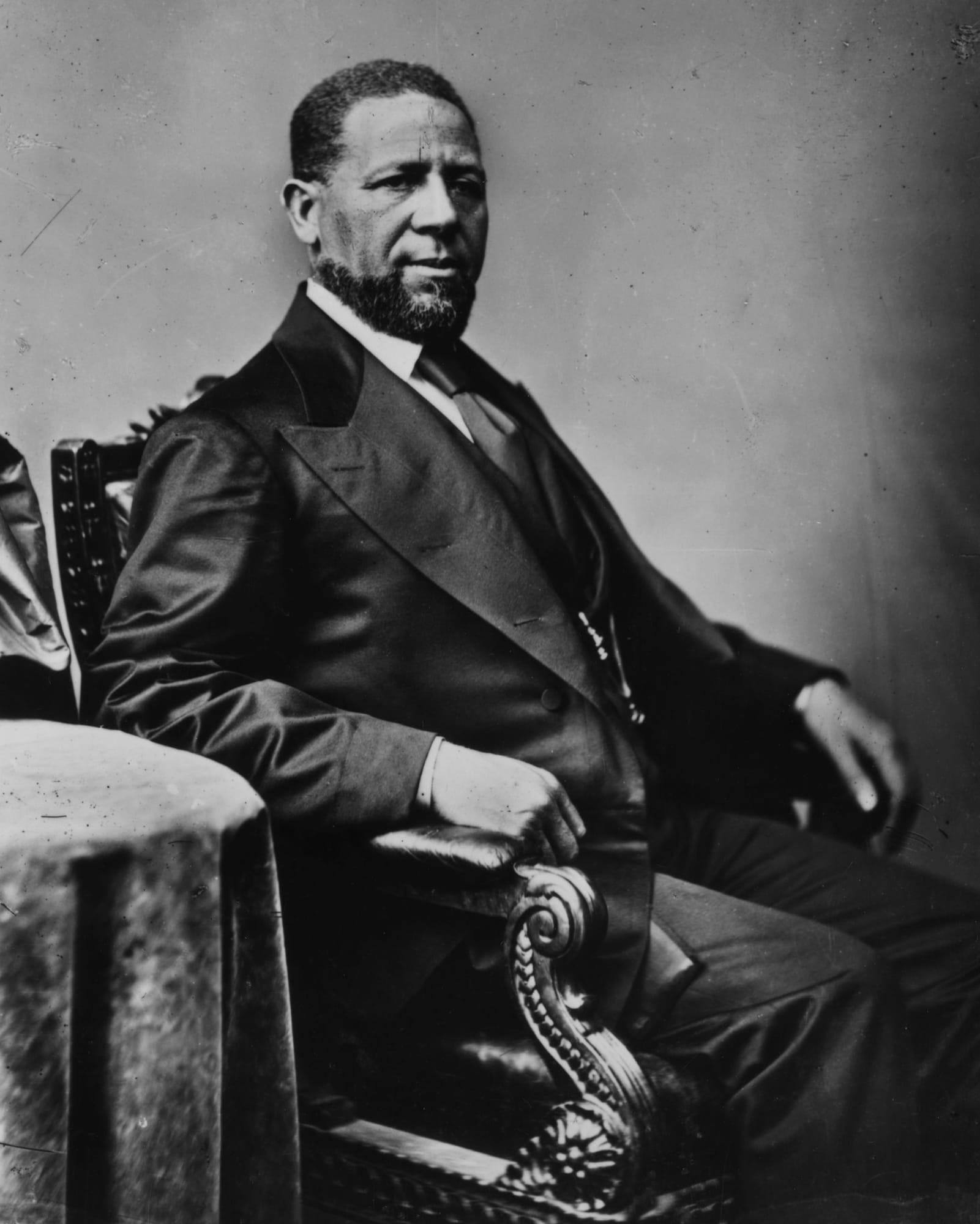

Hiram R. Revels (1ST African American to serve in the United States Senate.

Hiram Rhodes Revels arrived on Capitol Hill to take his seat as the first black member of the U.S. Congress in 1870. But first, the Mississippi Republican faced Democrats determined to block him.

The Constitution requires senators to hold citizenship for at least nine years, and they argued Revels had only recently become a citizen with the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment. Before that, the Supreme Court had ruled in its 1857 Dred Scott decision that black people weren’t U.S. citizens.

This technicality wasn’t actually their main issue with Revels. At the time, the Democrats were the party of white southern men, and they simply didn’t want any black men in Congress.

In any case, their bad faith legal argument didn’t hold up. Revel’s fellow Republicans argued he was born a free man in the United States and had lived there all his life. Dred Scott was a bad decision that should’ve never been made, which the Civil Rights Act and 14th Amendment had sought to redress, they argued. Just because the law had only recently recognized black men’s citizenship didn’t mean he was a “new” citizen.

“Mr. Revels, the colored Senator from Mississippi, was sworn in and admitted to his seat this afternoon,” reported The New York Times on February 25, 1870. “Mr. Revels showed no embarrassment whatever, and his demeanor was as dignified as could be expected under the circumstances. The abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of any one.”

“It really does reflect what a revolutionary period Reconstruction was,” says Gregory Downs, a history professor at the University of California, Davis. Congress had ordered the Army to register black southern men to vote in 1867. “In a series of a few months, you had people…in South Carolina and other places who had been slaves as recently as two or three years before now participating, now voting and even being elected to serve to remake the Constitution.”

The large population of formerly enslaved people meant that there were many more black voters in the south than the north (and actually, some northern states didn’t enfranchise black men until after the southern states). Black men elected black representatives and white Republicans locally and at the state level, which led to representation at the federal level.

But the people who had objected to Revels joining the Senate were still mad, and it was only a matter of time before backlash struck. In the 1870s, organizations like the White League and the Red Shirts began terrorizing and intimidating black men so they wouldn’t vote and participate in government.

That too came under attack as Jim Crow laws, poll taxes and other racist measures spread throughout the south. “The 1890s and early 1900s is where you get the laws that aim to permanently exclude virtually all black voters from participating,” Downs says. “The final black congressman from the south is George White who gives his farewell address, the phoenix speech, in 1901.”

After White, there were no more black Congress members from the original 11 Confederate states until 1973, when Andrew Young, Jr., of Georgia and Barbara Jordan of Texas (both Democrats) took their seats. Jordan’s election was particularly significant as she came just after New York’s Shirley Chisholm became the first-ever black Congresswoman in 1969—a full century after emancipation.

Shirley Chisholm

Pioneering African-American politician Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005) began her professional career as a teacher. She served as director of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center until the late 1950s, then as an educational consultant for New York City’s Bureau of Child Welfare. In 1968, Chisolm became the first African-American to earn election to Congress, where she worked on the Education and Labor Committee and helped form the Black Caucus. In 1972, she made history again by becoming the first black woman of a major party to run for a presidential nomination. After serving seven terms in the House, Chisholm retired from office to become a teacher and public speaker.

Born Shirley St. Hill on November 30, 1924 in New York City. Chisholm spent part of her childhood in Barbados with her grandmother and graduated from Brooklyn College in 1946. She began her career as a teacher and earned a Master’s degree in elementary education from Columbia University. She served as director of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center from 1953 to 1959 as an educational consultant to New York City’s Bureau of Child Welfare from 1959 to 1964.

In 1969, Chisholm became the first black congresswoman and began the first of seven terms. After initially being assigned to the House Forestry Committee, she shocked many by demanding reassignment. She was placed on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, eventually graduating to the Education and Labor Committee. She became one of the founding members of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1969.

Madam C.J. Walker

Who Was Madam C.J. Walker?

Madam C.J. Walker invented a line of African American hair products after suffering from a scalp ailment that resulted in her own hair loss. She promoted her products by traveling around the country giving lecture-demonstrations and eventually established Madame C.J. Walker Laboratories to manufacture cosmetics and train sales beauticians.

Her business acumen led her to be one of the first American women to become a self-made millionaire. She was also known for her philanthropic endeavors, including a donation toward the construction of an Indianapolis YMCA in 1913.

Early Life

Walker was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, on a cotton plantation near Delta, Louisiana. Her parents, Owen and Minerva, were recently freed slaves, and Sarah, who was their fifth child, was the first in her family to be free-born.

Minerva died in 1874 and Owen passed away the following year, both due to unknown causes, leaving Sarah an orphan at the age of seven. After her parents’ passing, Sarah was sent to live with her sister, Louvinia, and her brother-in-law.

The three moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1877, where Sarah picked cotton and was likely employed doing household work, although no documentation exists verifying her employment at the time.

Daughter A’Lelia Walker

At age 14, to escape both her oppressive working environment and the frequent mistreatment she endured at the hands of her brother-in-law, Sarah married a man named Moses McWilliams. On June 6, 1885, Sarah gave birth to a daughter, A’Lelia.

When Moses died two years later, Sarah and A’Lelia moved to St. Louis, where Sarah’s brothers had established themselves as barbers. There, Sarah found work as a washerwoman, earning $1.50 a day — enough to send her daughter to the city’s public schools.

She also attended public night school whenever she could. While in St. Louis, Breedlove met her second husband Charles J. Walker, who worked in advertising and would later help promote her hair care business.

During the 1890s, Sarah developed a scalp disorder that caused her to lose much of her hair, and she began to experiment with both home remedies and store-bought hair care treatments in an attempt to improve her condition.

In 1905, she was hired as a commission agent by Annie Turnbo Malone — a successful, black, hair-care product entrepreneur — and she moved to Denver, Colorado.

Madam C.J. Walker Company

While there, Sarah’s husband, Charles, helped her create advertisements for a hair care treatment for African Americans that she was perfecting. Her husband also encouraged her to use the more recognizable name “Madam C.J. Walker,” by which she was thereafter known.

In 1907 Walker and her husband traveled around the South and Southeast promoting her products and giving lecture demonstrations of her “Walker Method” — involving her own formula for pomade, brushing and the use of heated combs.

Walker Agents

As profits continued to grow, in 1908 Walker opened a factory and a beauty school in Pittsburgh, and by 1910, when Walker transferred her business operations to Indianapolis, the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company had become wildly successful, with profits that were the modern-day equivalent of several million dollars.

In Indianapolis, the company not only manufactured cosmetics but also trained sales beauticians. These “Walker Agents” became well known throughout the black communities of the United States. In turn, they promoted Walker’s philosophy of “cleanliness and loveliness” as a means of advancing the status of African Americans.

A relentless innovator, Walker organized clubs and conventions for her representatives, which recognized not only successful sales, but also philanthropic and educational efforts among African Americans.

Harlem Years

In 1913, Walker and Charles divorced, and she traveled throughout Latin America and the Caribbean promoting her business and recruiting others to teach her hair care methods. While her mother traveled, A’Lelia helped facilitate the purchase of property in Harlem, New York, recognizing that the area would be an important base for future business operations.

Walker quickly immersed herself in the social and political culture of the Harlem Renaissance. She founded philanthropies that included educational scholarships and donations to homes for the elderly, the NAACP, and the National Conference on Lynching, among other organizations focused on improving the lives of African Americans.

She also donated the largest amount of money by an African American toward the construction of an Indianapolis YMCA in 1913.

6,831 total views, 0 views today